Development of self-control and response inhibition

Society places a high expectation on children to control their impulses and their emotional expressions.

There is evidence¹ that those who develop strong self-control in early childhood are more successful in school. They are also more likely to go on to have successful careers and strong family relationships in adulthood.

So how do we understand this developmental process? What do we know about it?

Self-control begins to develop around 3 years of age. Before this, young children are frequently impulsive in their actions. They are often driven by emotions produced by the brain's 'emotion-generator' (the amygdala).

Research² indicates that, by the age of 4 years, children are beginning to exert some control over their actions. This self-control continues to notably increase to between 5 and 6 years and then it slows somewhat. As self-control skills develop, the child is able to attend to on-going tasks without the need for rewards, and they are increasingly able to make more careful plans.

Girls tend to develop self-control sooner than boys do, but this difference tails off from 9 years of age in typically developing children.

These age-related findings correlate with the stages of brain development. Our executive functions are skills which are carried out by the front part of the brain behind the forehead (frontal lobe). Brain development studies have shown that this area grows, strengthens, and matures significantly from the ages of 5 to 7 years. It is thought that this maturation of the nerves in this part of the brain is closely related to the development of self- and impulse-control.

Impulse control is otherwise known as the executive function skill of 'response inhibition'.

What about poor self-control?

When self-control doesn't follow the developmental trajectory outlined above, we see that the child's brain continues to use the established pre-existing brain pathways which are emotion-based (generated by the amygdala).

Children display poor control by acting more directly and impulsively, and they are focused towards immediately available cues and rewards.

Poor self control which persists into adolescence is commonly associated with poorer academic outcomes, ongoing impulsivity, risk-taking and thrill-seeking behaviours. In adulthood, there is an increased risk of poor outcomes such as physical health problems, substance misuse, financial difficulties, and criminal-offending.

The influences of factors beyond age and biology on self control and response inhibition, such as parental approach and school systems, are not well-researched.

What we do know, however, is that Executive Function skills, such as response inhibition, can be learnt, just like any other skill.

We also know that different types of Response Inhibition are likely to be carried out by different parts of the brain. For example, problems with motor response inhibition (involuntary movements), as seen in Tourette's Syndrome will be different from the brain pathways involved in emotion self-control which is what I am mainly focussing on here.

How about self-control in children with ASD, ADHD, et al ?

In my professional experience, delays in Executive Function skill development are common across all neuro-developmental conditions, although there has been very limited formal research examining this.

This does not mean that all children with Autism, ADHD, et al have difficulties across all their Executive Functions. Not at all. It means that knowing where your child's specific individual strengths and weaknesses lie will give you insights which allow the targeting of strategies and skill-building activities where these are lacking.

Returning to self-control and response inhibition, the commonest time for parents to bring their child to my clinic with these types of difficulties was between 8 and 9 years of age. It was evidently clear to them, and to others involved in the child's care, that they had not mastered the skill of self-control as expected (typically 5-6 years old). Meltdowns, outbursts, inconsolable crying, aggression, and other behaviour responses were reported. At this age, this can have a significant impact on a child's quality of life and their family and peer relations.

How do I learn more about my child's Response Inhibition skills?

Formal assessment and screening tools used by Occupational Therapists and other health professionals, like the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF2) by Gioia, Isquith, et al, can provide a helpful overview of your child's Executive Functions in general.

If you don't have access to this sort of professional input, or you want to know more about and understand your child's Response Inhibition specifically, I have developed a checklist to help with this.

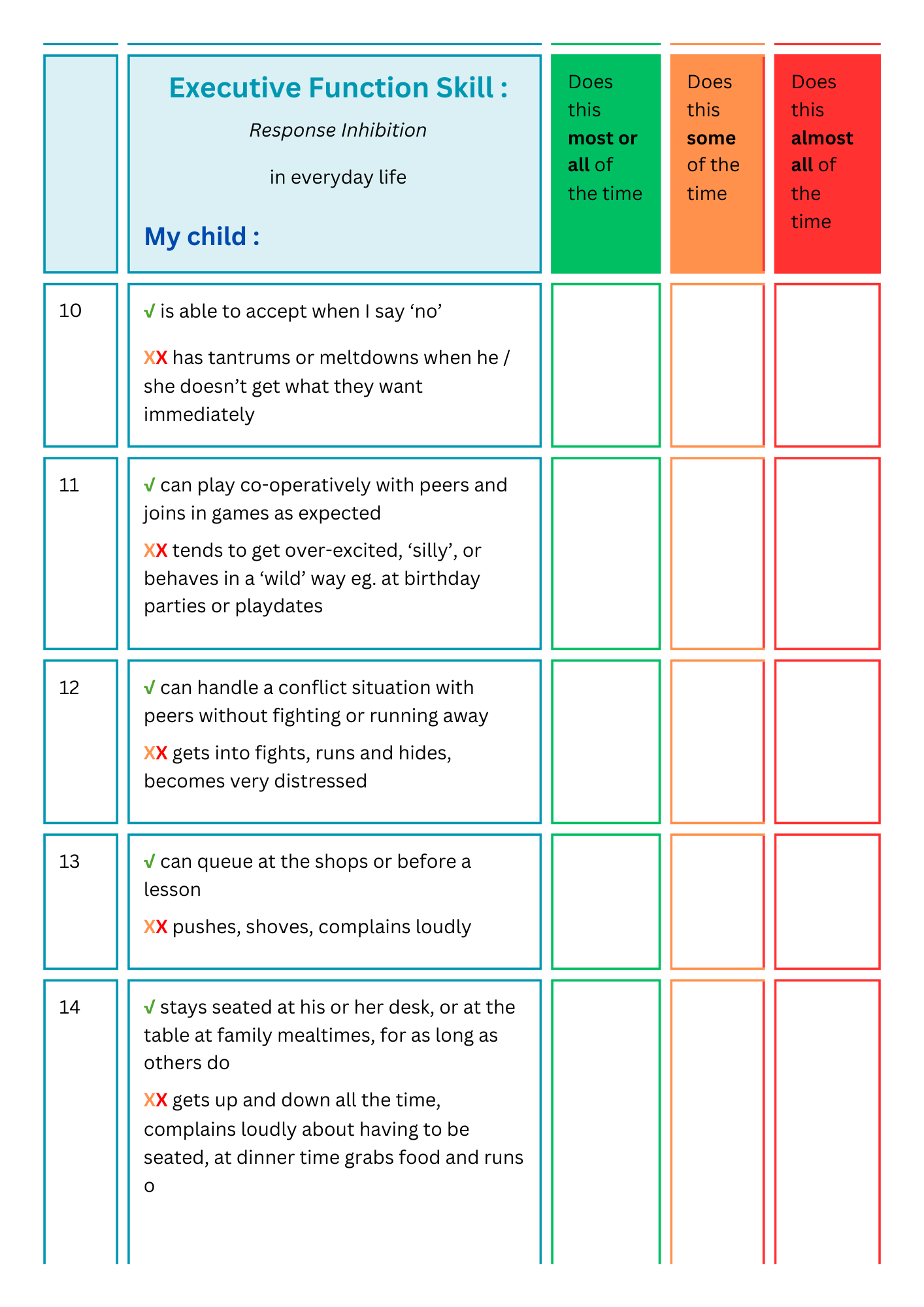

The Strengths and Challenges Checklist for Impulse Control (Response Inhibition) skills is a questionnaire which allows you to rate your child's responses in 26 everyday life situations. These range from social, emotional and sensory factors, to the cross-over with other executive functions, and safety-critical skills.

A brief interpretation guide is included, as well as a summary section to note your child's strengths and areas of weakness.

It can be added to your child's Skillset Portfolio if you have one.

Who is the checklist for?

Parents of :

- Children with Autism, ADHD, and other neuro-developmental conditions

- Primary-school aged children (6 - 12 years). If your child at the lower end of this age range they will still be developing some of these skills. It may be suitable for young teens too

- Children with persistent Impulse Control issues in any setting.

It is not indicated for children with:

- severe Autism Spectrum Disorder

- a Learning Disability

- Global Developmental Delay

- little or no awareness of others in their environment

- vey limited communication skills

Sample page from the checklist

The Response Inhibition checklist : terms and conditions of use

The checklist makes use of ‘practice based evidence’, in that they are common difficulties I have observed in my own clinical practice. It has no formal or informal research basis and has no population norms. Its intended purpose is for individual informational and educational purposes only. By using this checklist you are agreeing that : a) you understand the limitations as described above b) the author may modify or remove this product at any time

You are welcome to make copies of this checklist to share with others caring for your child.

¹ Moffitt T, Arseneault L, Belsky D et al. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety PNAS (2011) vol 108 (7) available at https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.1010076108

²Tao T, Wang L, Fan C, Gao W. Development of self-control in children aged 3 to 9 years: perspective from a dual-systems model. Sci Rep. 2014 Dec 11;4:7272. doi: 10.1038/srep07272. PMID: 25501669; PMCID: PMC5377018.